The debate resolution for October 2012 was as follows:

Resolved: Developed countries have a moral obligation to mitigate the effects of climate change.

I loved that resolution - it combined the three of the most intriguing things into one resolution: what should developed countries' governments do, what is a moral obligation, and what's the whole deal with climate change?

One thing to keep in mind is the difference between moral obligations and supererogatory ethics, which are things that one does not due to a requirement or obligation, but because they wish to go "above and beyond the call of duty." So while it's your moral obligation to not kill someone under normal circumstances, it is not your moral obligation to go out of your way to help a stranger who dropped their papers. But here's the problem: even though most people would agree with what I just said, the feeling's not universal. There are perfectly well-reasoned philosophers who say that any time you can help someone in greater need than you, you are obligated to help them (look up Peter Singer).

Well, after a month of researching and debating (I actually did rather well with that resolution), I came up with two strong arguments that I can proudly say I thought up:

- CON: Let the market solve. Essentially, the price of oil is increasing and will only continue to increase in the future. This means that renewables are becoming more and more economically viable. Since companies will do what is profitable to themselves, it follows that when renewables become better economic choices than fossil fuels, companies will go green. In fact, some estimates say Britain will see grid parity for solar power (when solar power becomes cheaper than electricity from non-renewable sources) within this year. What this means is that the problem will be solved because of the basic rules of economics. And what that means is governments don't have a moral obligation to mitigate climate change because it would be supererogatory. It would be nice if they helped out, and they certainly could, but they do not have an obligation to mitigate climate change because they don't need to be the mitigating actors.

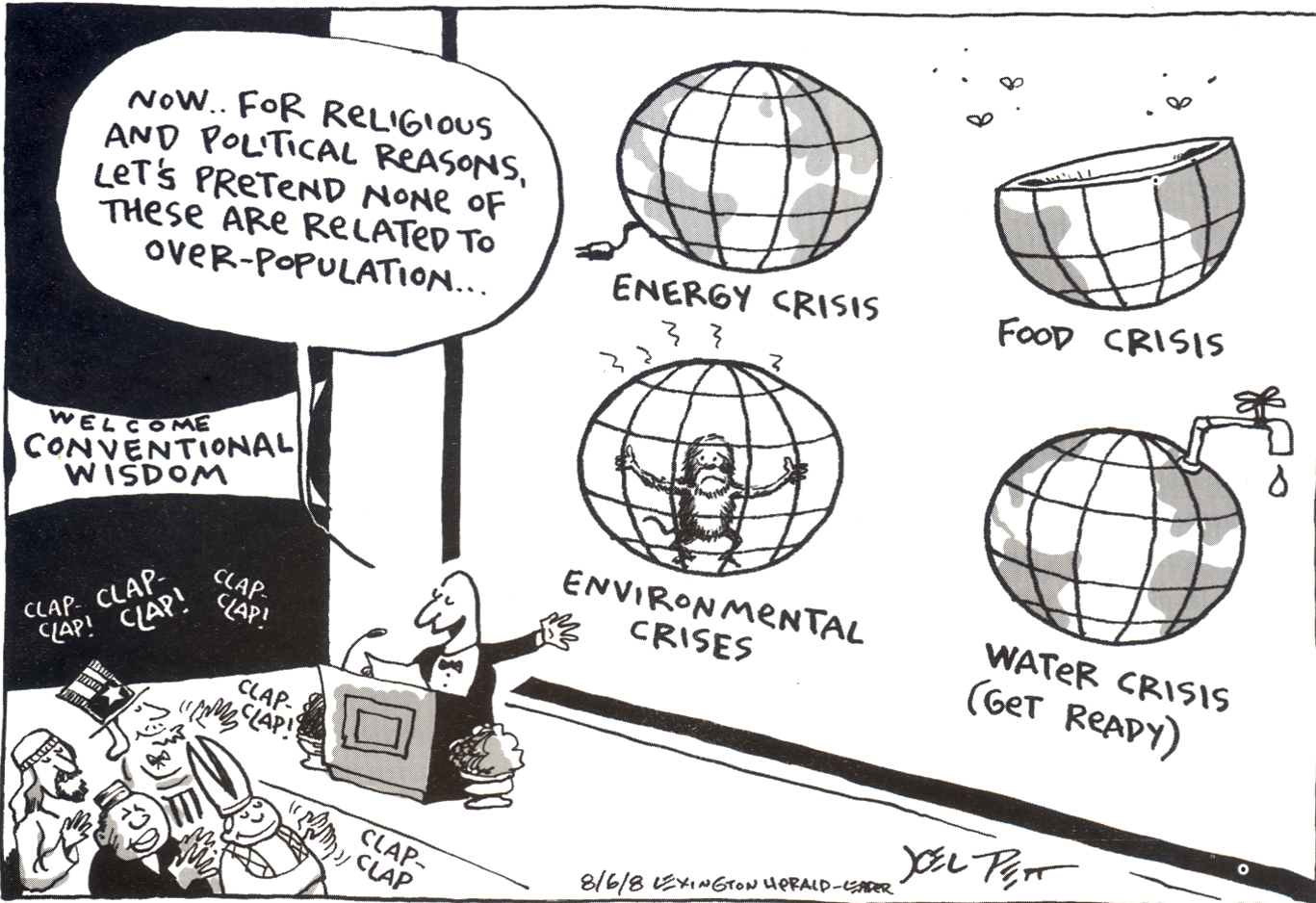

- PRO: Governments have the moral obligation to mitigate climate change because only governments can fix the core problems that are responsible for climate change. For example, my AP Environmental textbook points to things like human population growth as the core problems, and other issues, such as CO2 emissions, as direct or indirect results of those core problems. My argument is that "population growth" can't be solved effectively by anyone but the government. I'm not necessarily referring to drastic policies like the One-Child Policy; I mean family planning initiatives and laws concerning the education of young women, along with the advertisement of birth control to poor people. Non-profit simply don't have the budget or influence to do these things. Corporations - especially under a capitalist system - have no incentive to fix societies problems, especially when the return on their investment will not be profitable to them. Thus, the government is morally obligated to act because only it can effectively solve the problem.